Whilst struggling Tunisians decide to leave the country through irregular channels due to high unemployment and inflation, those arriving from abroad suffer even more severe challenges and discrimination. Neither a National Migration Strategy nor a National Institute for Refugee Protection has been capable of protecting those passing through Tunisia or trying to adopt it as their new home.

By Nesreen Yousfi (edited by Tijani Abdulkabeer)

Geographic location, political turmoil, and serious economic challenges have placed Tunisia at the heart of migration flows towards Europe. The North African country has become both a significant source of migration and an essential path towards richer countries for people fleeing conflict, persecution, and poverty in different parts of Africa and Asia. Recent numbers provide a clear picture of the situation. According to the World Bank, Tunisians were the main nationality to arrive in Italy via the Central Mediterranean Route between 2019 and 2023.

Furthermore, data collected by Arab Barometer in 2022 reveal that 45% of Tunisians want to emigrate, more than double the 2011 rate (22%). Of those who want to leave the country, 41% are willing to do so without the appropriate documentation. Similarly, Tunisia is a common passage for sub-Saharan African migrants trying to reach Europe. The World Bank says that in the first eight months of 2023 44% of irregular migrants going to Europe had travelled from Tunisia to Italy.

Only 11% were Tunisian; the remaining were sub-Saharan. Whilst the migrants’ option of using the country as a stepping stone highlights its proximity to Italian islands, the decision taken by Tunisians to migrate irregularly, in spite of the high risks of fatality during the perilous journey, reflects their desperation to improve their quality of life.

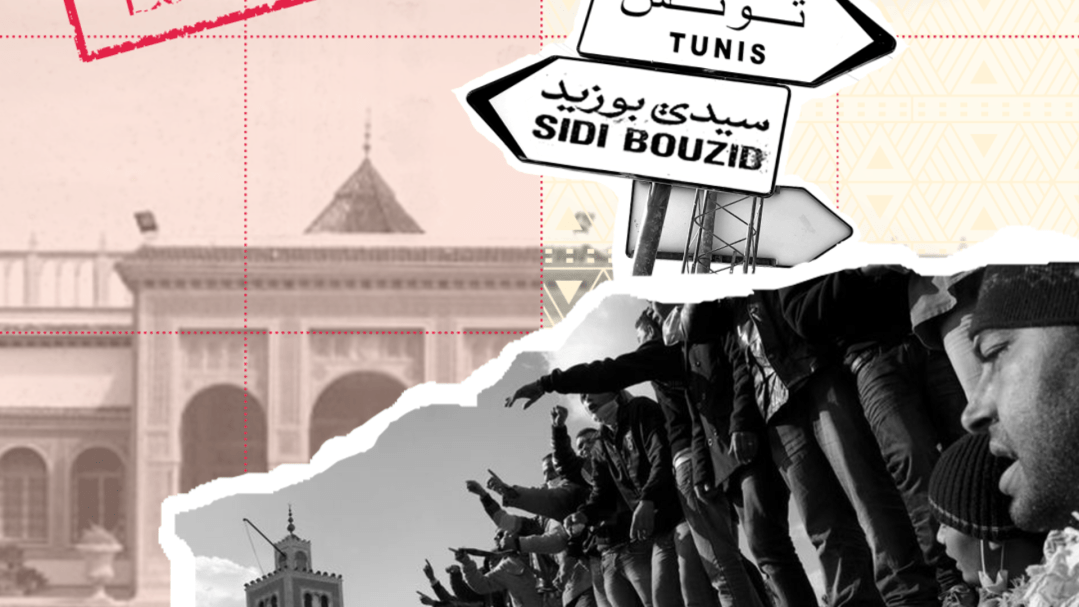

Political turmoil and a struggling economy

More than 13 years have passed since the young Tunisian street vendor, Mohamed Bouazizi, took his own life in response to the confiscation of his merchandise – and his livelihood – by authorities, police brutality, and subsequent state neglect. Only 26 years old, Bouazizi had spent most of his life working to support his family, selling fruits and vegetables in the streets of Sidi Bouzid, central Tunisia. His tragic self-immolation was followed by street demonstrations against authoritarian rule and socio-economic conditions.

This further led to the Jasmine Revolution and the wider Arab Spring. In contrast to other countries with popular uprisings in the region, Tunisia was able to take much larger strides towards democracy. After the autocratic President Ben Ali fled to Saudi Arabia on 14th January 2011, the country established a new constitution and shifted towards a multiparty system. Nevertheless, the economic situation has remained dire. As of the fourth quarter of 2023, the national unemployment rate is at 16.4%, but even higher for women, at 22.2%.

Higher education graduates, the majority of whom are between 20 and 29 years of age, are particularly touched by unemployment, with 23.7% of them without work as of the second quarter of 2023. Female graduates are more than twice as likely to be unemployed. There are also deep regional inequalities between the rural inland and the move developed coastal areas. Partnered with a long-term drought which has raised food inflation to 13.9%, these trends of high unemployment, in addition to gender, age, and regional disparities, are on par with the precarious living conditions which motivated the Jasmine Revolution.

The tourism sector, which contributed 4.5% to Tunisia’s GDP in 2019, has suffered from fluctuations via the revolution, the 2015 Islamic State (ISIS) attack on tourists, the COVID-19 pandemic, and spillover from the civil war in neighbouring Libya. The industry had a relatively fast recovery from the initial drop in tourism after the terror attacks and has now also returned to pre-pandemic levels. However, the decline of the Tunisian Dinar, in tandem with wider structural issues in the sector, has limited its potential revenues. As the situation bites harder, the country has turned heavily on foreign debt, which in 2022 alone was close to 90% of its GDP.

Having been able to repay 2023 debts, Tunisia still faces challenges securing more external funding. According to the Ministry of Finance, debt servicing is expected to increase by 40% in 2024 compared to 2023. To stabilise Tunisia’s economy, in 2023 the African Development Bank Group (AFDB) suggested the country should adopt a medium-term strategy to reduce sovereign debt, implement a plan to restructure public enterprises, and reduce its external debt. It also advised the country to negotiate a plan with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to restore fiscal sustainability, in order to attract more investment.

Hard for Tunisians, harder for foreigners

While local citizens turn elsewhere for survival, foreign migrants have either decided or been forced to remain in Tunisia, despite initially wanting to reach Europe. One hurdle preventing their moves has been the Memorandum of Understanding between the European Union and Tunisia to cooperate on border management. In his study on migrant protection in Tunisia, urban studies researcher Adnen El Ghali notes that “EU funding to Tunisia is conditional on the country playing its part in stopping migrants reaching European soil”.

This ultimately turns Tunisia into a permanent destination for many, as the Tunisian government has augmented its role in managing irregular migration. Although Tunisia established the National Migration Strategy (2012) and the National Institute for Refugee Protection (2018) to defend migrant and refugee rights, the reality indicates the country has been falling short of carrying out that duty. Tunisia’s Labour Code legislates that work permits expire annually, ultimately restricting their access to long-term employment. Since many migrants overstay their visas, they are then unable to renew their work and residency permits.

This results in several migrants holding irregular status in the country, unravelling into a chain of dead-ends, as without residency permits, migrants do not have access to basic amenities like public health care, travel, or defence against exploitative employers. Labour exploitation of sub-Saharans in Tunisia is hence rampant. An absence of work permit and irregular status leads them to end up in informal employment (e.g., through a verbal contract).

It is possible, for instance, that many sub-Saharan Africans are finding work in the hospitality sector which has an unusually high informal employment rate (46% in the second quarter of 2019). Such working conditions ultimately leave migrants at a much higher risk of exploitation at work. On top of that, sub-Saharan migrants and refugees are at increasing risk of state and non-state violence. Although Tunisia’s economic problems pre-date the growing migrant population, discourse in the sociopolitical sphere has shifted towards scapegoating sub-Saharan migrants and refugees for the country’s social woes.

Despite the adoption of an anti-racism law in 2018, President Kais Saied has been fanning the flames of racial tensions, claiming last year that the influx of sub-Saharan Africans is a plot between opposing parties and foreign nations to change the demographic composition of Tunisia – despite the fact that foreign migrants make up around 0.5% of the population, a significant number of whom come from Syria. This government’s rhetoric, regarded as racist and condemned by most of the international community, has led to an escalation in violence against sub-Saharans. When undocumented migrants are subject to violence in Tunisia, their lack of civil status discourages them from coming forward as they are afraid of being arrested, or being subject to police corruption and extortion, a dynamic which echoes the tragedy of Bouazizi in 2010.

In a podcast with Specto Studio, Filippo Furri (anthropologist and member of the Migreurop network), underlines the violent expulsion of migrants since Saied took the reins of the presidency. These concerns are confirmed by a joint statement from the UN agencies UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, and IOM (International Organisation for Migration) last summer, reporting that hundreds of migrants had been abandoned in the desert along the Algerian and Libyan borders. Many are even forced across the borders where they are faced with Algeria’s military or Libyan militias who violently refuse them entry.

This chain of offloading responsibility for migration from Europe to Tunisia, and then to neighbouring Algeria and Libya, leaves sub-Saharan migrants in a society already struggling to provide for itself. Stuck in Tunisia and scapegoated for the country’s wider socioeconomic issues, sub-Saharans ultimately become the most vulnerable to the country’s poor economic conditions, as their unrecognised status exposes them further to violence and exploitation.

This article is part of the special series “Tunisia – Land of Passage”, produced by Specto Media and aidóni. Listen to the podcast here.

This multimedia series is produced by Specto Média. Author: Eléonore Plé Investigation and production: Eléonore Plé Sound production: Norma Suzanne Graphic identity: Amandine Beghoul and Baptiste Cazaubon French version dubbing: Yamane Mousli English version dubbing: Isobel Coen and Julian Cola Editing: Hugo Sterchi and Norma Suzanne Recording studio: Radio M’S

To discover the series in French, visit Specto Media

This multimedia series is produced in collaboration with aidóni for translation, and producing the articles and profiles.

One thought on “Hardship in Tunisia breeds tension between locals and migrants”