Life came to a standstill in the usually chaotic Hai Mayo neighbourhood of Juba, with school children, motorcyclists, and business owners all standing on the streets discussing the murder of Anthony Surur.

By Richard Sultan

On 31 March, Surur, a 62-year-old engineer, was shot dead as he was jogging en route to St Theresa’s cathedral for morning mass. “But why, why! Why jog in the morning?” an elderly man whispered to his friend as they made their way out of the crowd. “This western mentality, at that age, he should have known better than jogging in the morning—that is a White’s thing.” As his words of caution suggest, incidents such as the unfortunate shooting of Surur have become a common occurrence for most residents of Juba and its outskirts.

Lokwilili is a Boma in the Luri Payam, on the outskirts of the capital Juba. Bomas are the lowest administrative unit in South Sudan, which usually comprise a few villages, and Payams are the second-lowest administrative units, which contain several Bomas. In the immediate aftermath of the peace deal, Lokwilili used to be a crime zone like most suburbs in the city. “There used to be daily reports of robberies and killings in 2019,” Justin Tombe, a youth leader from Lokwilili, recalled. “The police were ill-equipped and understaffed to deal with the rampant crime cases, a situation which has only slightly improved now.” Over the next three years, a unique community policing initiative transformed the neighbourhood.

According to the youth leader, in December 2019, two weeks before Christmas, the Lokwilili chief—a government-appointed head of a Boma—called upon every resident to attend a mandatory meeting. “My dear people! I called for this urgent meeting for us to jointly find a solution to the endless robberies and killings in our Boma,” chief Yohana Lokule said in his opening remarks. After several deliberations, Tombe said, it was decided that every family head would sit in groups of ten, comprising their closest neighbours.

Tombe recalled the chief Lokule’s instructions: “Learn and master the names, occupations and dependents of the ten family heads who live near you so that you can help each other in case of anything. You will also identify leaders among your group who will organize a silent vigilante group from the youth to police your neighbourhood of ten families every night besides screening any new resident.”

Tombe explained the formation and functioning of the community vigilante groups. In every group of ten households, first all the able-bodied youth were identified. The group leader then divided them into sub-groups of two or three—depending on the area size of the ten households—and every night those sub-groups remained on duty, staying awake through the night to alert the community and the police, in case of any incident.

When the chief asked for the names of the group heads to be submitted to him, he was expecting the worst response from those who might be armed. “What the chief did was put the suspected criminals in charge of the security,” Deng Thon, a retired brigadier of South Sudan’s People’s Defence Forces, explained. “Put differently, the chief doesn’t know which of his residents are armed or not, a scenario that isn’t surprising in South Sudan considering the history of independence struggle and the recent civil wars. As a result, to succeed, you need authority, condition and inclusivity which the chief used perfectly. In this case, the condition is failure to participate puts you at risk of being singled out as the real criminals. What then becomes impossible if all the people who are armed in a neighbourhood start caring for each other”

Tombe added, “In South Sudan, the organized forces—such as the police, army, National Security and intelligence officers—all reside together with civilians as there are no designated barracks of residence for them. As a result, the chief anticipated some form of resistance.” Gesturing to the surrounding hills, Tombe apologised as his line of thought shifted towards trying to understand the chief’s concerns. The rocky Kujur hills, a name that loosely translates to ‘witch’ or ‘evil,’ is often referred to by the locals as the genesis of everything good and bad about Lokwilili. Apart from hosting festivities of different religious sects, providing the only free source of employment through stone quarrying, and being a free daily natural gym for fitness lovers; the hills are also a hiding ground for some notorious gangs, according to the police.

The chief’s actions, might be a gamble. Yet, residents of Lokwilili would testify how that meeting from 2019 has changed the fortune of this once-isolated Boma, which has transformed from a sparsely populated neighbourhood to a crowded but safe place.

“Today, our small trading centre operates until 2 am local time and sometimes till the next morning on big days compared to 7 pm back in the day,” Tombe said. That is in spite of the absence of government electricity, functioning with just a few generators that run up to 10 pm. The few police officers in our area have also grown in confidence due to our level of cooperation with them.”

Mama Meling Ann, a 41-year-old widow who sells tea and other snacks at the Lokwilili trading centre believes there is power in collective responsibility. “Let me tell you, my son, it has been nearly four years since I lost my husband to the unknown gunmen. He was a guard in the city with one of the security companies. Ohhh! Dear Tom, how I miss you.” The perpetrators are still at large and motives again not established, but Ann has not lost hopes of justice. “One day, trust me! One day, they will face justice,” she said. “My only comfort now is that things have changed for the better, and my husband is one of those who sacrificed for it.”

Lokwilili is not the only South Sudanese effort with community policing. The United Nations has been involved in training community police groups in other localities such as Cuei-Cok and Aweil. In both areas, the community policing system is under the leadership of the South Sudan National Police Service, which established Police Community Relations Committees comprising volunteer members who are vetted by the police. The PCRCs then collaborate with local authorities, ensuring greater cooperation and coordination on policing efforts.

According to Thon, the retired brigadier and a veteran of the 21-year struggle for independence, the Lokwilili initiate is far more effective than the others in the country. Unlike other community policing initiatives in the country, “Lokule made it mandatory for every residence regardless of one’s military or security sector affiliation,” Thon said. “Anyone who violates the rule will be considered a criminal and subject to expulsion from the neighbourhood.” Thon attributes the success of the Lokwilili initiative to this tough stance of the chief.

The Lokwilili initiative was not implemented without hurdles. There were initial difficulties in the beginning because some residents were armed and some were not. Some officers in the police force were also reluctant to cooperate because of some individuals being armed. It’s common knowledge that in South Sudan, most of the police and their Criminal Investigation Department officers isolate themselves from the public. They love to be feared instead of being trusted to earn the population’s respect.

“Some of the armed residents are members of the security forces,” Tombe said. “Even if some of the police suspect them of being in a criminal network, there was no evidence, and none of them is a victim to date,” he added, which supports Deng’s analysis of the initiative’s success.

The armed residents also complained about the burden of protecting families other than their own. But when most of the community moved forward with the initiative, others joined in. According to Tombe, there was one night when a community vigilante member was wounded, and the other members of the group arrested the criminals before they could escape. “It was our first real encounter with the criminals after several near misses, and our actions sent shock waves among the criminal networks,” Tombe said, adding that in 2019 alone, they netted about 15 criminals.

Another reason behind the initiative’s success has been that most residents of Lokwilili are poor and live with a sense of trust, despite working various occupations and being from different ethnicities. “In the uptown end of Juba City, where some residents are well off compared to others, there is little cooperation as there is no sense of being a community,” Tombe said. “That is why it’s difficult to replicate this method in most residential areas.” Deng also added the advantage of the Boma’s establishment on communal land pending title deeds from the government, something that most residents will want the chiefs help in.

“There are still issues of night robberies and isolated killings on the roads that lead to Lokwilili which we believe is easy to overcome once the government extends electricity to our area,” Tombe said, with his hands wide open to depict the unknown hope of power reaching their area.

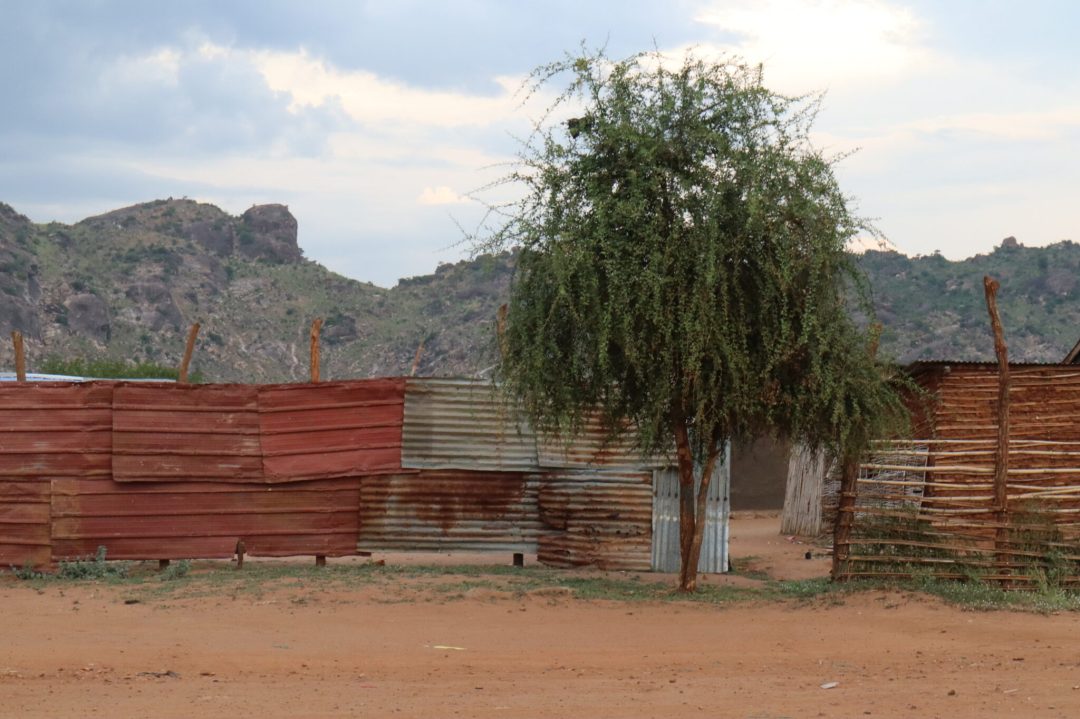

Top image: The road leading to the Lokwilili market in the city of Juba (Credit: Richard Sultan)